Les ervaringen / Interviews

Les ervaringen en Interviews

1. Corrie Schouten

2. Anneke Strik

3. Luciette van Hezik

. Interview JONAS MAGAZINE / Atelier de ‘Werkplaats Molenpad’ in Amsterdam / The Netherlands

5. Een Ode aan het belang van de doorstroming via de hersenbrug van de Linker en Rechter Hersenhelft

A research: My Stroke of Insight / Dr. Jill Bolte Taylor

Een wereldberoemd onderzoek naar een casus van een neurologisch ziektebeeld bij een Amerikaans Neuroloog

1. Interview met Corrie Schouten in het Jonas Magazine nummer 57 mei 2002

Dit geeft de effecten en het commentaar weer van de groepsleerkracht en de kinderen met betrekking tot de toepassing van de oefeningen van ´t Tijdloze Uur van Michiel Czn. Dhont.

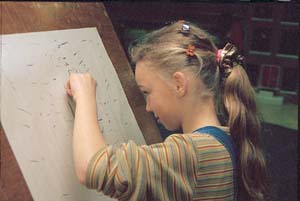

In het speellokaal van basisschool De Vijzel in Heerhugowaard ligt een lang stuk papier op de grond en daarachter zitten negen leerlingen naast elkaar. Ze zijn allemaal 7 tot 8 jaar oud.

Ze hebben twee zakken met potloden uitgezocht om mee te tekenen, één voor de linker en één voor de rechter hand. Ze zullen zo meteen beginnen om met beide handen te tekenen. Met gesloten ogen en op het ritme van de muziek.

Corrie Schouten, niet alleen adjunct-hoofd van de Vijzel, maar ook kleuterleidster en remedial teacher voor motorische problemen, zet de muziek aan.

Niet lekker in hun vel

Volgens Corrie Schouten hebben deze kinderen uit groep drie en vier een zwakke motoriek en concentratieproblemen. Het ene kind iets meer van het ene probleem, het andere kind iets meer van het andere probleem, maar allemaal zitten ze niet lekker in hun vel.

Elke week heeft ze de groep meer dan een half uur. De les begint altijd met bewegen op de muziek.

Corrie Schouten geeft deze lessen al tien jaar. Ze gebruikt verschillende methodes en sinds ongeveer een jaar gebruikt ze de werkmethode van het in 2000 gepubliceerde ´´t Tijdloze Uur´.

Corrie Schouten: “Dan kun je jezelf zijn. Bij het tekenen met beide handen worden beide hersenhelften gestimuleerd omdat de linker hersenhelft de rechterhand aanstuurt en vice versa. Ondertussen horen de kinderen de muziek, door het sluiten van de ogen sluiten ze de buitenwereld buiten. Er is geen contrôle van de handen via de ogen. Dit stimuleert het gevoel. Daardoor zijn ze tegelijkertijd in verschillende gebieden actief. Ze voelen, ze horen, ze bewegen, ze reflecteren.

Het komt er op neer dat de kinderen door de oefeningen hun eigen vaardigheden op zowel cognitief als emotioneel gebied leren herkennen en gebruiken. Leerling Bas over de oefening: “Met mijn ogen dicht en met de muziek kan ik goed nadenken. Over hoe je met het potlood over het papier gaat bewegen. Dat vind ik leuk. Je denkt nergens anders aan.” Daniza vindt het uitvegen van het potlood leuker: “Dat voelt zacht.”

Net als aan het begin van de les, toen de vuisten nog schoon waren, voelen ze de ene hand met de andere. Het is stil, alleen de geluiden van het schoolplein dringen in het speellokaal door. Na een paar minuten mogen de ogen geopend worden. Wat hebben ze gevoeld? Voelt het anders dan daarvoor toen ze nog niet met potlood hadden getekend? Nigel : “Mijn nagel is nog glad.” Linda wijst naar haar handpalm: “Dit is zacht geworden. En warm. En een beetje plakkerig. “ Robin voelt niets. “Helemaal niets?” vraagt Corrie Schouten. ´Nee.´ “Zijn ze warm? Of koud?” Robin, nadat hij een paar seconden heeft nagedacht: “Warm.” En in antwoord op de volgende vraag of hij verder niets voelt, na nog een pauze: “En zacht.”

’t Tijdloze Uur met groep 4/5 van een basisschool in Amsterdam’.

Blokkade

Later zegt Corrie Schouten hierover: “Toen Robin ernaar werd gevraagd begon hij van alles te voelen. Mijn doel is dat hij over een jaar de vraag naar wat hij voelt zonder hulp zal beantwoorden. Op dit moment heeft hij nog een blokkade: “Ik voel niets”. Volgens haar hebben speciaal perfectionistische kinderen moeite om zomaar iets te tekenen. “Zojuist, toen we begonnen met tekenen op muziek, vroeg één van de kinderen me zachtjes wat hij moest tekenen. Maar we gaan niet “iets” tekenen, we gaan alleen maar tekenen.

Perfectionistische kinderen willen dat de tekening mooi is. Dat is de linker hersenhelft die opspeelt. Die zegt min of meer :”Dit is de juiste manier en dat niet. “ De tekenoefening is niet bedoeld om een mooi huis te tekenen. De oefening is bedoeld om de emotionele kant van de leerlingen te stimuleren. Net als het voelen van hun handen. Je maakt ze bewust van dat gevoel door ze daarmee te laten werken. Het is anders dan de tafel van drie leren. Dat is ook belangrijk, maar dat is de linker hersenhelft. Die wordt de hele dag door geactiveerd. Een andere keer oefen je het voelen bijvoorbeeld door het klei kneden. De kinderen doen ontdekkingen. Ze ervaren bewust dat er meer is dan alleen hun hersenen. Dat hun lichaam allerlei soorten zintuigen heeft die ze kunnen benoemen, voelen en toepassen. Ik merk dat het op deze manier werkt doordat uiteindelijk de kinderen zelf beginnen te praten over wat ze voelen. “

Leerlinge Daniza vindt het “voelen” het fijnste. “We hebben het ook met klei gedaan. Dan moet je kneden en dan uitwisselen met iemand anders uit de groep. De klei van die ander voelde zo anders. Dat was grappig.”

Hoe merkt Corrie Schouten dat de kinderen met een oefening beter in hun vel komen te zitten?

Schouten: “Het gebeurt vaak dat ze, nadat ze intensief bezig zijn geweest en klaar zijn, zeggen: “Dat was fijn juf, wanneer kunnen we dat weer doen?” Ze voelden zich op hun gemak, ze waren zichzelf gedurende die periode van meer dan een half uur. Wat kun je nog meer bereiken? Natuurlijk gaan ze na de tekenoefening terug naar hun normale les. En dan is er weer meer dan genoeg aandacht voor het cognitieve. Maar zelfs als ze een onderwijzer hebben die een aantal jaren enkel de cognitieve kant stimuleert, als de balans tussen emotie en verstand eenmaal geïntroduceerd is, zullen ze die nooit meer kwijt raken. Het valt me op als ik ze weer zie, soms jaren later.”

2. Anneke Strik / Docent aan opleidingen en groepsleerkracht / kinder -tekendocent / annekestrik@versatel.nl

‘Na mijn opleiding BVE ben ik in het onderwijs gaan werken. Daarnaast heb ik de opleiding creatieve handvaardigheid gevolgd.

Verder heb ik HBO Jeugdwelzijnswerk en Antropologie gestudeerd. Aan de Kolam (tekenschool voor kunst en communicatie) heb ik de studie kinder -tekendocent gevolgd.

Op het atelier van de Werkplaats Molenpad heb ik bij beeldend kunstenaar / docent Michiel Czn. Dhont diverse workshops gevolgd van uit de methode ’t Tijdloze Uur’.

‘In mijn onderwijs praktijk heb ik vele tekenlessen aan kinderen gegeven. Veelal in naschoolse opvang. De kinderen die ik heb

begeleid waren tussen de 6 en 10 jaar. Soms waren er wat meer jongere kinderen in de groep. Soms wat meer tienjarigen.

Elke les begon ik met een oefening uit ’t Tijdloze Uur. De kinderen wisten ook altijd dat ik begon met zo’n oefening en ze waren vaak nieuwsgierig welke oefening, omdat het steeds weer een verrassing was. Ze gingen vaak ook erg lachen om deze oefeningen’.

Enkele voorbeelden / ontspanning en weer openstaan voor nieuwe ervaringen

‘Ik heb een aantal oefeningen gebruikt zoals de oefening met de ritmische puntjes. De kinderen kwamen vaak net van school en moesten ook echt nog ontladen. Daar was deze oefening heel geschikt voor. Het effect was dat de kinderen zich ontspanden, veel lachten en open stonden voor een nieuwe tekenopdracht en ontdekking’.

‘De oefening de Lemniscaat heb ik ze in verschillende toepassingen laten maken.

Ook heb ik de kinderen op muziek met de andere of niet-dominante hand laten tekenen en met gesloten ogen laten tekenen.

Het belangrijkste resultaat was ontspanning en weer openstaan voor nieuwe ervaringen’.

Plezier in de oefeningen

‘Daarvan kan ik een goed voorbeeld geven. Een moeder van een van mijn leerlingen, een meisje van ongeveer 8 jaar, kwam naar me toe en vertelde dat haar dochter zich altijd zo verheugde op de tekenlessen. Ze bleek een nare tijd gehad te hebben in de klas en ze kon nog maar weinig plezier beleven. Het tekenen deed haar zichtbaar goed. De oefeningen uit het boek ’t Tijdloze Uur hebben daar zeker toe bijgedragen omdat ze een belangrijk onderdeel vormden van mijn lessen’.

Aan Pedagogisch medewerkers heb ik les gegeven die de opleiding SPW3 – MBO volgden om met kinderen in de kinderopvang te werken. Regelmatig deed ik met deze volwassenen de klei-oefening om ze intuïtief te laten boetseren met gesloten ogen. Dat deed ik om ze te laten ervaren welke ontwikkelingsgebieden bij kinderen gestimuleerd worden door ze met klei intuïtief te laten boetseren met gesloten ogen.

Ik geef nu lessen aan PW4 opleiding (pedagogisch werker 4) en ik wil deze studenten tijdens de opleiding leservaring geven over de methode ’t Tijdloze Uur.

Graag wil ik aan deze pedagogisch medewerkers het belang overbrengen van de combinatie van de klei-oefening en de verschillende motorische tekenoefeningen. Door het zelf te ervaren, zien ze het pedagogisch belang om kinderen de ruimte te geven om hun eigen beeldtaal te ontdekken. Ruimte voor onderzoek is voor kinderen zo belangrijk. Het draagt bij aan de versterking van hun creativiteit. De ontwikkeling van de beeldtaal is een verrijking van het algemeen creatief vermogen van kinderen. Het heeft zijn uitwerking op de algehele vorming van het kind als intelligent bewust handelend mens.

annekestrik@versatel.nl

‘Oefening met het kleibolletje’. Het kind ervaart en oefent de motorische interactie tussen de rechter en linker hand. Dit creëert een betere doorstroming tussen de twee hersenhelften via de Hersenbrug. De oefening kan solo uitgeoefend worden en tevens in uitwisseling tussen kinderen in een groep/klas. Daarbij ervaren kinderen de temperatuur, het gewicht, de vochtigheidsgraad en het volume van het kleibolletje en dat het per hand verschillend kan zijn en ook per persoon in het uitwisselen tussen de kinderen onderling (Zie in het boek de Sensomotorische oefeningen van Al Pesso en de hand-oog coördinatie van Lev Vygotsky).

(door Michiel Czn. Dhont)

3. Luciette van Hezik / Tutor / Therapist / luciettevanhezik@zonnet.nl

Below my experience and vision regarding your methodology of ’t Tijdloze Uur.

I want to offer an example of the counseling of adults where drawing out of movement and modeling with clay have had far-reaching results through a combination with Social Artistic Therapy.

In an individual counseling I met a woman who had the feeling in her life that she was stuck in a set pattern, where verbal therapy did not provide the desired results.

Out of the basic locomotion I guided her to the swaying balance movement, where she herself felt the need to work towards ‘The writing”, specifically the staccato. In the alternation of staccato and melodic movement memories and images began to surface of an isolation chamber where she had spent time 16 years ago when she was admitted due to post natal depression.

Feelings of powerlessness, sadness and anger surfaced, but also her expression of power, which surprised her and also gave her a liberated feeling. When I asked her which animal she could experience in this, she modestly indicated a cat, but in reality is was more like a lion! Through the task out of social artistic therapy to build a lion out of yellow clay, she has step by step been able to give a form to her snowed under force and has integrated it into her daily life.

I want to link my experiences of the 3 year courses in creative visionary processes by Michiel Dhont with my study at the College at Leiden: Social Artistic Therapy (SAT), visual 4th year. The SAT has been developed within the anthroposophic health care where the aim is towards a total view of man, in which individual qualities and personality are important starting points for the therapy. In its therapy SAT uses visual arts, painting, drawing and modeling.

Another possibility for me to integrate Michiel Dhont’s method is in learning to express my own individuality. As my thesis I want to do a study into the effect of using both hands as well as only the right and left hand with all the visual techniques of SAT to stimulate the halves of the brain which can occasion a complete harmonisation of man in his healing process.

luciettevanhezik@zonnet.nl

(Translation: Liesbeth Rientjes)

—————————————————————————————————–

3. JONAS MAGAZINE

Art put into service of ‘wholeness’

– for children as well as adults –

An interview by Inge Evers, journalist,

visual artist (Amsterdam, The Netherlands)

with Michiel Czn. Dhont, author of ‘The Timeless Hour’ – 22 exercises for the benefit of the integration of the cognitive, emotional and social intelligence.-

Art Expressive Work: “One of the essential aspects of drawing and painting in general, is the fact that one gets to be confronted with a totally blank, usually white sheet of paper or cloth, or with an empty fully open space. Briefly: to be on the Spot and in the Now.” elementary expression in space primal rhythm “White paper has a way of looking at you, I always feel when I start by going for a new piece of paper. Even more so when it is sitting there in the typewriter. On top of that it gives me the feeling that it should stay neat and that I am not supposed to mess in the margin. So, I still write an article first by hand, with a lot of crossings and references, exclamation marks, stars and other signs of which I am the only authority. I knew I wasn’t the only person, but after this interview I am convinced that it is quite normal, yes even essential.”

Inge Evers, Amsterdam

‘One of the essential aspects of drawing and painting in general, is the fact that one gets to be confronted with a totally blank, usually white sheet of paper or cloth, or with an empty, totally open space. That very confrontation evokes a tension which can cause something into being, something that can actually give birth. However, it can also happen during that first phase that a person meets with his or her deepest fears. One feels as if one jumps into an empty swimming pool, not knowing whether the pool is fille with water or not. Fear often leads to ‘closing up’ entirely, in a way that nothing is coming out any longer. But a person can be taught how to deal with situations like this. A person can learn how to let go off himself and give in to a pure motion without fear of failing. A person can learn to feel comfortable in emptiness, eventually that person can intuitively do something with that emptiness. The paper has patience and doesn’t cause accidents.”

Speaking is Michiel Dhont from Amsterdam, an all-round artist and musician, who, besides creating works of art and performing music, has developed a specific way of teaching for children as well as for adults. In his Molenpad Studio he offers various courses as:orientation-techniques, drawing, acrylic painting, clay modeling, collages and life-model drawing.

These courses are all based upon his own method: drawing and painting done through motion by intuition. Among his students one frequently find artists from various disciplines who got stuck in their flow of ideas. Those who have taken his lessons find in general they have a healing effect and stimulate towards an inner growth to inspire directly their art expressive flow.

The method, the motion in it, is intensely related to everyting he has done and developed during his life. It is intensely related to his own emotions.

“Several years I have done things I didn’t really want to do. I was miles away from my own feelings.”

In 1963, when he was 23 he left for Mexico and the USA, just to be alone. In that tranquility and time-lessness he found himself again. He drew a lot and made music and he knew he wanted to be an artist.

Mrs. Joosten, his teacher at the Montessori school had advised similarly to his parents in those days. However, that advice was not taken seriously. On the contrary, Michiel was sent to another school. He still remembers her radiation “She was the only person who actually saw me as I was as a child.” In her class the foundation was laid for a creative development later on. Without that experience he would not have had the courage and the confidence at twenty three to switch from his study in economics to ‘Visual Arts’. Back in Holland from a long tour through the USA and Mexico he embanked upon Ateliers ’63 in Haarlem, in those days by far the most interesting art academy in The Netherlands.

Michiel continued his education with M.O.A. and M.O.B. in Amsterdam in masters degree in teaching arts. He intended to earn a basic living by teaching. To be independent had his highest priority and he knew as an artist it would not be easy to survive in the world of free arts.

“Sometimes it is frustrating and difficult, but perhaps that is what I need. If all of a sudden I would have no financial problems as an artist, I would never give up teaching, teaching is a very essential part of me. I grow just as much in working with people, as people grow in their work they do with me.”

expressive, ritmic and passionated

expressive, ritmic and passionated

When he finished teachers’s college he continued his study at the Rietveld Academy, Amsterdam, in sculpture, under Jos Wong and Aart Riethoek for a period of one year. Six years after he stood up in the General Education system before he got out. As long as he remembers during his time at teachers college there have been people asking him to teach them. In the course of the years the number of people increased. This gave him enough confidence to start as an independent small entrepeneur when in 1975 he had found a large attic at his desposal at the Molenpad in Amsterdam.

In 1975 he founded the Werkplaats Molenpad Studio in Amsterdam. “A lot of work had to be done before we could start, there wasn’t even daylight and not a single pipe or wire. Now all equipment is there including full daylight.”

Michiel first put a lot of energy in acquisition to start with students, which finaly succeded. Something Michiel discovered “Only rarely some people could express their real, pure inner pictures in the drawings and the paintings. I could see the difference in my own art work where I always have been able to express my inner pictures. How could I find a way to give my students the tools to do so?”

“I let it hang as a questionmark above my head. Through meditation I received the images shown on this page, which I drawed spontaneously on a piece of paper laying next to me. On the sheet I discovered the variety of sketches based on left handed and right handed drawing. When this had happened a world opened. I felt a strong connection to these images. I did realize that it became a basic structure from where other pictures could rise. This basic structure has always been very simple. From that moment I felt the left hand drawings as an important image to develop. Al this grew to an introduction in my courses toward expressive art through movement and from intuition.”

From then of it started that students started to creaate original images of a variety in left- and righthand drawing by movement simultaniously or in exchange of one and the other hand.

Michiel started out to bring into practice specific exercises during his classes. These exercises were mainly focused on ‘centring’, meaning: to bring into balance, to achieve equilibrium. When a person is in balance or equilibrated he has a connection hetween the left and right hemisphere, the large back muscle functions flexible and both feet are well grounded. This may sound theoretical and perhaps far from attractive. However, proof to the contrary and speaking from experience have recorded part of a drawing lesson focussed on script …

Course-members enter the workshop slightly out of breath due to climbing all those steps. They take their own paintbox, brushes and painting clothes out of the cupboard as they proceed to prepare everything for the course. At the start there is still some talking, but eventually everyone works in silence. In order not to have to interrupt oneself all the time, one usually hangs three or four sketching sheets and one drawing sheet on top of each other over the drawing board. Charcoal and chalks are handed out, pots are being filled with water for painting later on in the afternoon. Nearly every one walks on socks or on slippers.

Before Michiel starts his course he gives a short explanation of things to come. The theme is the script – the motoric script – that will be used starting from writing into drawing. “There are two types of script”, Michiel says, “the melodic, (continuous) connecting script, and the rhythmic staccato script. Both types can be combined with one another in a later phase, and/or used very freely in regard to one another. That is called the harmonic script.”

Michiel suggests to start with one script at the time, the melodic script. One doesn´t need to work constantly towards the right, one is allowed to refer back into the writing motion. He does advise to stay on the sheet. Which is not necessary with the rhythmic script. One starts to work with one hand in columns, when a column is filled one starts again on top of the sheet and writes through the existing signs. example of a staccato script example of a more complex script example of a melodic script example of a harmonic script which combines rhythmic and melodic script Michiel joins in with his students, often whith his eyes closed. Meanwhile he makes remarks in order to make his students aware of what they are doing.

“Feel your feet, feel the ground, (re)move your feet in accordance with your arms and with the way your hand moves over the sheet. Take a comfortable distance between you and your sheet.” “Don´t get too close. Let the non-drawing arm hang relaxed along your body. Loosen your shoulders, also drop the shoulder of the writing arm. Go three, four, if necessary five times over the same line. Occasionally you should grab back with your charcoal as though you are writing away from you.” From time to time he repeats these remarks. Other than the scratching of the charcoal over the sheets and an occasional tooter of a boat passing by the canal, there is not a single sound.

More directions are given when Michiel starts to look around. “Try to stand a more with your body on your basin/pelvic. Losen your arms, keep your head free into space when you feel tension, continue freely for a while in your own rhythm. Take your charcoal and try once to move across the sheet. Do not try to keep up anything. See it as a play. There´s no need to write ten sheets full.”

One senses the reactions to his slow almost monotonous voice.

In the intermediate silences one hears the charcoal scratching again. “When you feel tension, slow down a little and exhale all the way.”

This time, when he askes to feel a sound, there is more volume to it than the first time. One can actually hear tones. Again Michiel indicates a number of things, such as disconnecting the head, directed to the sheet, towards a horizontal position of the head. It will take away the control function of the eyes and will let your hands move free to express. The pressure on the charcoal may vary.

“Relax, also behind your eyes and behind your forehead. Go easy about changing your feet. Direct your attention towards the earth. In between try and make a melodic motion across the entire sheet to the left and try to alternate these movements.”

At a given moment the right hand joins in and everyone works two-handedly. Now everyone works as he likes. And so it lingers on. After a while he has them change the charcoal from the right hand to the left hand. On a new sheet the same exercise is repeated writing from right to left with the left hand.

“Draw with your hand in a slanted way from below. Loosen your right arm. Let go off your thought.”

Towards the end of this exercise Michiel has everyone visualise the two lines in which can be written with large signs and with eyes open.

“Write continuously in an undulating melodic way”, he says again and “feel the musical sounds of the movements. You should be able to feel yourself inside. Listen to that melodic sound. Let it become an interaction with the motion of your hand. Bring that sound up, outward. Keep it to yourself, no need for other to hear it.”

Michiel gives a few examples: left – right in reverse, parallel, big small or small/big simultaneous. “Let it be a large feeling of writing. Let the sound come up again. Work in a quasi (pseudo) nonchalant manner.” Then we draw with two hands and a few minutes later we are drawing with one hand and we alternate hands.

We have to do less and less. Continually half of the half of the half and so on. The transition of an exercise in drawing toward painting should go in a gradual and shelve like manner. Occasionally you let your hand go off the sheet, sometimes left, than right. The instructions keep coming.

“Bring the action from one hand to the other. Take a little distance from the sheet by stepping backward and continue working within that space. Stay in motion. Go easily about filling up the space between you and the sheet. Keep looking at your hands and close your eyes. Alternate those actions too. Now you can feel quite involved, evoked by the inner easing of the tension, in such a way that you can react very directly and impulsively, straight from the gut.”

“Loosen up your belly muscles while diminishing all movements. Now make a transition to the next sheet.”

Michiel is now quietly explaining, that while exercising rhythmic writing one is allowed to write of the sheet. Everyone is totally involved now, no one seems to get out of concentration or look at his watch. A timeless concentrated quietude is reigning. An exercise like this one lasts about 25 minutes. When they/we talk to each other some later it seems as though everyone is coming from his/her own world and it is not easy to actually snap out of it. Everyone is sitting on the floor in a circle. If anyone feels the need to talk about what he or she felt during the work, they can speak up. After that everyone turns to painting and once again it is very quiet in the studio.

His lessons were partially inspired by his experience with Tai Chi. “Historically one can say, to put all things together, that someone like the artist/tutor Johannes Itten from the Bauhaus (Germany 1922) was a true pioneer in the period after the first world war because he introduced basic movements from the East into his lessons. He was one of the first peop1e who actually instructed to combine the two hemispheres.” That might very well be the main reason why he no longer connected with Bauhaus, which eventually grew more and more into Functionalism. There is the Frenchman Merleau-Ponty, who became well known for his intuitive drawing script. And Betty Edward, who wrote a book: ´Drawing from the right side of the brain´ (read : drawing with the left side (hand) of the body).

All the exercises Michiel developed and exposes to children and adults, make it possible for children as well as adults to express themselves from their intuition in true pictures by drawing and painting.

4. Een Ode aan het belang van de doorstroming via de hersenbrug van de Linker en Rechter Hersenhelft

A research: My Stroke of Insight / Dr. Jill Bolte Taylor

Een wereldberoemd onderzoek naar een casus van een neurologisch ziektebeeld bij een Amerikaans Neuroloog Dr. Jill Bolte Taylor

Dr. Jill Bolte Taylor, the Singin’ Scientist

My Stroke of Insight is a New York Times Bestseller and is published by Viking Penguin Group. You may order a copy through online stores including Amazon and Barnes & Noble, or ask your local bookstore. It is available in hardcover, audio, and large-print edition.

Jill Bolte Taylor was a 37-year-old Harvard-trained and published brain scientist when a blood vessel exploded in her brain. Through the eyes of a curious neuroanatomist, she watched her mind completely deteriorate whereby she could not walk, talk, read, write, or recall any of her life. Because of her understanding of how the brain works, her respect for the cells composing her human form, and an amazing mother, Jill completely recovered her mind, brain and body. In My Stroke of Insight: A Brain Scientist’s Personal Journey, Jill shares with us her recommendations for recovery and the insight she gained into the unique functions of the right and left halves of her brain. Having lost the categorizing, organizing, describing, judging and critically analyzing skills of her left brain, along with its language centers and thus ego center, Jill’s consciousness shifted away from normal reality. In the absence of her left brain’s neural circuitry, her consciousness shifted into present moment thinking whereby she experienced herself “at one with the universe.”

Based upon her academic training and personal experience, Jill helps others not only rebuild their brains from trauma, but helps those of us with normal brains better understand how we can ‘tend the garden of our minds’ to maximize our quality of life. Jill pushes the envelope in our understanding about how we can consciously influence the neural circuitry underlying what we think, how we feel, and how we react to life’s circumstances. Jill teaches us through her own example how we might more readily exercise our own right hemispheric circuitry with the intention of helping all human beings become more humane. “I believe the more time we spend running our deep inner peace circuitry, then the more peace we will project into the world, and ultimately the more peace we will have on the planet.”

My Stroke of Insight (Viking) is available at your local bookstore or online merchants including Amazon and Barnes & Noble.

For rights to My Stroke of Insight, please contact Ellen Stiefler by e-mail: Info@AmicusAgency.com or phone: 858-756-5767.

For press inquiries, please contact Louise Braverman, at louise.braverman@us.penguingroup.com.

For speaking engagements, please contact Dr. Katherine Domingo, at kat@mystrokeofinsight.com.

We have set up a forum for people who want to build a community around the ideas presented in the best-selling book. There is a forum for people who have experienced stroke or other medical issues first-hand or through a loved one; another forum focuses on techniques for how to achieve a balanced brain; and yet another allows people to share their stories of insight and the life lessons they have learned. These forums can be found on the website, www.mystrokeofinsight.com. Read beautiful stories and learn more about the ideas presented in My Stroke of Insight.